Why Do Gray Whales Migrate to Baja Mexico?

2023-09-29

Unveiling the Secrets of Gray Whale Migration

Imagine being a 45-ton gray whale living along the coast of British Columbia, where life is pretty good. There’s an abundance of food, including tons of yummy amphipods and shrimp. In fact, with your hearty appetite, you might devour up to 2500 pounds of these little critters every day. Your dining routine involves diving down to the muddy bottom, rolling over on your side, and bulldozing along the seabed, scooping up both mud and delectable treats. Your baleen-equipped tongue efficiently separates what you want from what you don’t. So, why do gray whales migrate to Baja, Mexico?

What Draws Gray Whales South?

In these waters, your only enemy is the orca, also known as the killer whale. However, you’ve discovered the joy of hanging out in the shallows, sometimes even in water as shallow as 15 centimeters, between the kelp forests and the shoreline. Orcas rarely venture into such shallow waters, making it a safe haven for you. While orcas are known for their playful breaching and jumps, they’re also cautious about getting stuck in these shallows. Any adult gray whale knows that one mighty swipe of their tail flukes can mortally wound an orca, earning them the nickname ‘devil fish.’

The Evolutionary Benefits of Baja’s Winter Waters

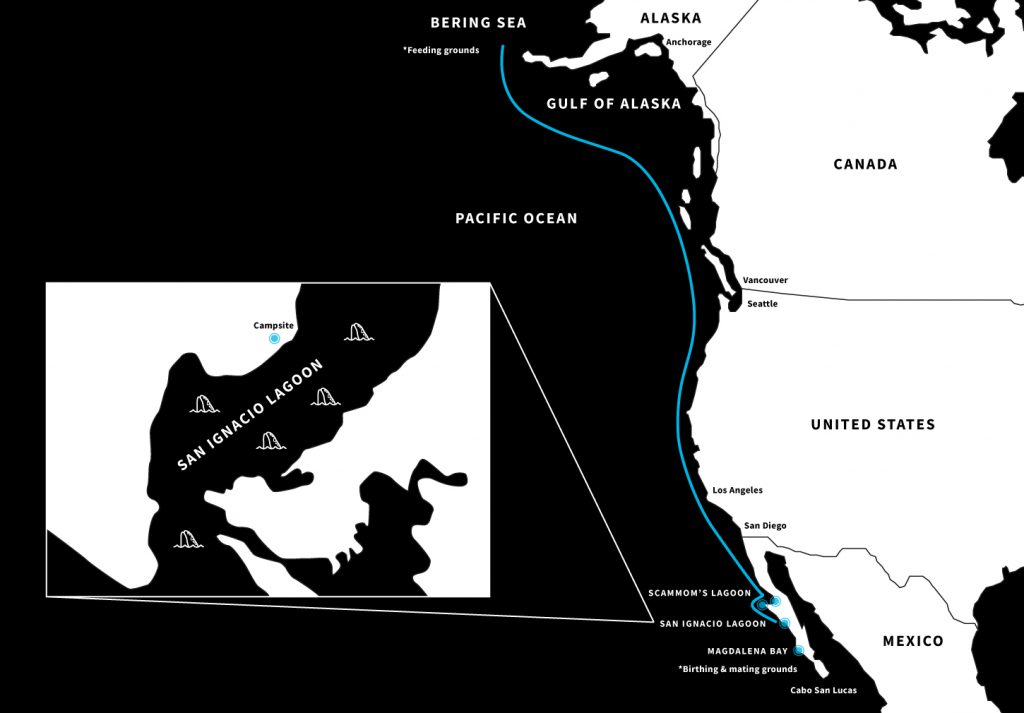

But now, imagine you’re a pregnant momma whale facing an intriguing dilemma. Why would you leave this idyllic place, where everything you need for survival is at your fins, to embark on a migration of 2000 to 3000 miles down the coast? This journey involves fasting, all while you carry your precious calf within. The caloric requirements for such a migration are immense, as you must swim thousands of miles and have enough fat reserves to nurse your calf. A calf typically grows 50 to 80 pounds a day during the 4 to 5 months spent in the lagoon in Baja Mexico. In fact, momma gray whales also nurse their calves all the way back up the coast, for a total nursing period of 7 months or longer, with milk astonishingly containing 53% fat (compared to 2% for humans).

So, why the arduous journey to Baja? One theory suggests that the higher salt content of the lagoon’s water may help the calves float more easily when they are newborns. However, other Baja birthing lagoons also have extensive salt flats. Moreover, mommas also give birth to calves in the open ocean on the final stretch of their southward migration, with reports stating that more than 50% of all births occur north of Los Angeles.

Perhaps the salt flats hint at something else – warm water. The lagoons are relatively shallow, which helps maintain even warmer water temperatures. Is there an energy benefit to the whales in these warmer waters compared to the frigid North Pacific? In winter, waters in the North Pacific can drop to 34-35°F in the Aleutians, while British Columbia remains relatively balmy at 46°F. By contrast, San Ignacio Lagoon might dip from 86°F in the summer to 74°F in the winter. The math is fascinating: a big female, after a summer of feeding, might weigh 90,000 pounds. The southward migration, calf care, and northward migration could cost her 30,000 pounds of blubber – about one-third of her body weight. Moreover, calves nurse on milk that is a remarkable 53% fat.

So, assuming warm water provides benefits, could there be more to this story? Orcas! While the thought of transient orcas lying in wait for gray whales during their Monterey Bay crossing is troubling, they are almost never seen in San Ignacio Lagoon. In February 2022, orcas entered the lagoon, causing concern. They took at least one dolphin (remains were found), but that was the first time they had been seen in the lagoon in 17 years. The orcas face a high-risk, high-reward situation. The entrance to the lagoon is tricky, with constantly shifting shallow sandbars. Gray whales are comfortable in the shallows, even when it’s wavy or there’s a swell. Orcas do not have the same comfort zone and could ground themselves, potentially leading to their demise. If they do enter the lagoon, they are in unfamiliar territory – it’s fairly shallow and home to a large seasonal population of big, powerful adult gray whales, known as ‘devil fish.’

We welcome all comments, additional ideas, and suggestions. Our working hypothesis for now is that gray whales migrate to the lagoons of Baja Mexico because the water is warm, has higher salt content, is shallow, and offers protection from orcas.

Of course, only our beautiful gray whales know the actual answer to this. We can speculate all we want, but the only thing we know for sure is that whales are highly adaptive and will likely survive long past humans. They have evolved from four-legged terrestrial animals into the elegant and incredible marine mammals we see today. As they continue evolving in front of our very eyes, adapting to avoid starvation and finding new ways to thrive, we remain humbled and in awe of these magnificent animals.

P.S. Yes, I know that it’s Baja California and not Baja Mexico! In 1804, the Spanish crown divided California into Alto (or upper), which is now California, USA, Baja California (sometimes now called Norte), and Baja California Sur (or south). San Ignacio Lagoon is just south of the dividing line and is located in BCS, but people often get confused by ‘California’ and think we’re somewhere near San Diego!